Forest Giant

A tree-climbing scientist and his team have learned surprising new facts about giant sequoias by measuring them inch by inch.

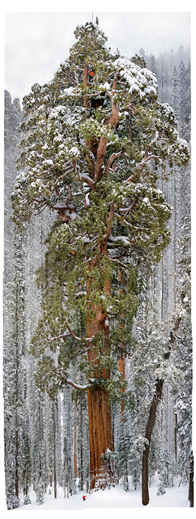

Sequoia in the Snow

They are so old because they have survived all the things that could have killed them.

Cloaked in the snow of California's Sierra Nevada, the 3,200-year-old giant sequoia called the President rises 247 feet. Two other sequoias have wider trunks, but none has a larger crown, say the scientists who climbed it. The figure at the top seems taller than the other climbers because he's standing forward on one of the great limbs.

Click here to Pan & Zoom

THE PRESIDENT

- HEIGHT: 247 feet

- AGE: at least 3,200 years

- DIAMETER AT BASE: 27 feet

- TOTAL VOLUME: 54,000 cubic feet

-

Shape

The President reached its current height well over a thousand years ago but continues to expand in volume of wood, its crown growing more intricate.

The top 40 feet of the main trunk, struck by lightning, has been dead for more than a thousand years.

-

Foliage

The scientists who measured every part of the tree estimate it has nearly two billion leaves and more than 82,000 cones. Each cone, the size of a chicken’s egg, holds about 200 seeds.

-

limbs

The four largest limbs range in diameter from five to nearly seven feet; the largest is about 60 feet long. The tree’s total number of branches: 534.

-

groves

Sequoias rarely grow in pure stands, but by sheer size they dominate their groves, which hold a variety of tree species.

Where the Giants Grow

A slender, 250-mile-long corridor on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada is the giant sequoia’s only natural habitat. No tree surpasses it in volume of wood. Fortunately, logging proved impractical, and in 1890 many of the titans gained protection with the creation of Sequoia and Yosemite National Parks.

GROVE DISTRIBUTION

All but 8 of the 67 identified sequoia groves lie south of the Kings River. These southern groves usually hold more—and larger—trees.NORTHERN LIMIT

Only six giant sequoias form this isolated old-growth grove. tap to explore the president tree

tap to explore the president tree

elevation cross section

elevation cross section

giant forest

giant forest

n a gentle slope above a trail junction in Sequoia National Park, about 7,000 feet above sea level in the southern Sierra Nevada, looms a very big tree. Its trunk is rusty red, thickened with deep layers of furrowed bark, and 27 feet in diameter at the base. Its footprint would cover your dining room. Trying to glimpse its tippy top, or craning to see the shape of its crown, could give you a sore neck. That is, this tree is so big you can scarcely look at it all. It has a name, the President, bestowed about 90 years ago by admiring humans. It’s a giant sequoia, a member of Sequoiadendron giganteum, one of several surviving species of redwoods.

It’s not quite the largest tree on Earth. It’s the second largest. Recent research by scientist Steve Sillett of Humboldt State University and his colleagues has confirmed that the President ranks number two among all big trees that have ever been measured—and Sillett’s team has measured quite a few. It doesn’t stand so tall as the tallest of coast redwoods or of Eucalyptus regnans in Australia, but height isn’t everything; it’s far more massive than any coast redwood or eucalypt. Its dead spire, blasted by lightning, rises to 247 feet. Its four great limbs, each as big as a sizable tree, elbow outward from the trunk around halfway up, billowing into a thick crown like a mushroom cloud flattening against the sky. Although its trunk isn’t quite so bulky as that of the largest giant, the General Sherman, its crown is fuller than the Sherman’s. The President holds nearly two billion leaves.

Trees grow tall and wide-crowned as a measure of competition with other trees, racing upward, reaching outward for sunlight and water. And a tree doesn’t stop getting larger—as a terrestrial mammal does, or a bird, their size constrained by gravity—once it’s sexually mature. A tree too is constrained by gravity, but not in the same way as a condor or a giraffe. It doesn’t need to locomote, and it fortifies its structure by continually adding more wood. Given the constant imperative of seeking resources from the sky and the soil, and with sufficient time, a tree can become huge and then keep growing. Giant sequoias are gigantic because they are very, very old.

They are so old because they have survived all the threats that could have killed them. They’re too strong to be knocked over by wind. Their heartwood and bark are infused with tannic acids and other chemicals that protect against fungal rot. Wood-boring beetles hardly faze them. Their thick bark is flame resistant. Ground fires, in fact, are good for sequoia populations, burning away competitors, opening sequoia cones, allowing sequoia seedlings to get started amid the sunlight and nurturing ash. Lightning hurts the big adults but usually doesn’t kill them. So they grow older and bigger across the millennia.

Another factor that can end the lives of big trees, of course, is logging. Many giant sequoias fell to the ax during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But the wood of the old giants was so brittle that trunks often shattered when they hit the ground, and what remained had little value as lumber. It went into shingles, fence posts, grape stakes, and other scrappy products. Given the difficulties of dealing with logs 20 feet thick, broken or unbroken, the trees were hardly worth cutting. Sequoia National Park was established in 1890, and automobile tourism soon showed that giant sequoias were worth more alive.

One thing to remember about them, as Steve Sillett explained to me during a conversation amid the trees, is that they withstand months of frigid conditions. Their preferred habitat is severely wintry, so they must be strong while frozen. Snow piles up around them; it weights their limbs while the temperature wobbles in the teens. They handle the weight and the cold with aplomb, as they handle so much else. “They’re a snow tree,” he said. “That’s their thing.”

Among the striking discoveries made by Sillett’s team is that even the rate of growth of a big tree, not just its height or total volume, can increase during old age. An elderly monster like the President actually lays down more new wood per year than a robust young tree. It puts that wood around the trunk, which grows wider, and into the limbs and the branches, which grow thicker.

This finding contradicts a long-held premise in forest ecology—that wood production decreases during the old age of a tree. That premise, which has justified countless management decisions in favor of short-rotation forestry, may hold true for some kinds of trees in some places, but not for giant sequoias (or other tall species, including coast redwoods). Sillett and his team have disproved it by doing something that earlier forest ecologists didn’t: climbing the big trees—climbing all over them—and measuring them inch by inch.

With blessings and permits from the National Park Service, they performed such high-altitude metrics on the President. This was part of a larger study, a long-term monitoring project on giant sequoias and coast redwoods called the Redwoods and Climate Change Initiative. Sillett’s group put a line over the President’s crown, rigged climbing ropes into position (with special protectors for the tree’s cambium), donned harnesses and helmets, and went up. They measured the trunk at different heights; they measured limbs, branches, and burls; they counted cones; they took core samples using a sterilized borer. Then they fed the numbers through mathematical models informed by additional data from other giant sequoias. That’s how they came to know that the President contains at least 54,000 cubic feet of wood and bark. And that’s how they detected that the old beast, at about the age of 3,200, is still growing quickly. It’s still inhaling great breaths of CO2 and binding the carbon into cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in a growing season interrupted by six months of cold and snow. Not bad for an oldster.

That’s the remarkable thing about them, Sillett told me. “Half the year, they’re not growing aboveground. They’re in the snow.” They grow bigger than their biggest compeer, the coast redwood, even with a shorter growing season.

It was fitting, therefore, that Michael (Nick) Nichols made his portrait of the President in snow. Nick and Jim Campbell Spickler, an expert climber and rigger, came up with a plan. With a crew of assistants and climbers drawn heavily from Steve Sillett’s team, they arrived in mid-February, when the snowbanks along the plowed road were 12 feet high. They rigged ropes on the President and on a tall nearby tree, both for human ascent and for raising cameras. They waited through blue skies, slushy conditions, and fog until the weather changed and the snow came again and the moment was right. They got the shot. (Actually there were many individual shots, assembled as you see on the poster.) By the time I showed up, they were packing to leave.

Nick had spent more than two weeks commanding this operation, composing the image and engineering it from the ground. But before the last ropes came down, he wanted to climb the tree himself. Not to take photos, he explained. “Just to say goodbye.” He put on a harness and a helmet, clipped onto a rope, fit his feet into the loops, clutched the ascender, and up he went.

Once Nick was down, I went up myself—slowly, clumsily, with help from Spickler. Ascending, I braced my feet gratefully against the great trunk. I stood for a moment, with Spickler beside me, on one of the huge limbs. After half an hour, I found myself in the crown of the President, 200 feet above the ground. I saw the big burls at close range. I saw the smooth, purplish bark of the smaller branches. All around me was living tree. I looked up, dizzily, noticing small cracks in the deadwood and channels of cambium that flowed between trunk and limbs like a river of life. I thought: What an amazing place. Then I thought: What an amazing creature.

Next afternoon, with Nick and the others gone, I snowshoed back to the President alone. There had been too much to take in, and I wanted another look. For a while I gaped at the tree. It was magnificent. Serene. It didn’t sway in the breeze; too solid to sway. I wondered about its history. I contemplated its durability and its patience. The day was warmish, and as I stood there, the President released a small dollop of melting snow from a high branch. The snow scattered as it fell, dissipating into tiny flecks and crystals, catching the light as they tumbled toward me.

“Gesundheit,” I said.